What if technology, instead of replacing humans, augmented our abilities to unleash ingenuity? What if we could govern organizations collectively — without leaders? What if we could solve problems and increase productivity at scales never imagined?

Many scenarios for the future of work are dull, or even alarming: amid dwindling resources, encroaching technology as a de-humanizing force, a busy workforce slowly replaced by AI and robots automating jobs.

It is beyond our Visions2030 team’s scope to speak as experts about jobs and the economy (we’re primarily in the imagination business). However, we do know the power of imagining new futures, to think broadly, to entertain even the apparently crazily irrational, to speculate vast possibilities. It is easy to create a future built out of fear — it is much more challenging to formulate desired goals to work toward, and consider them possible.

For example, instead of eroding human agency, perhaps technology might in fact usher in a new era of abundance — without leaving anybody out. Indeed, perhaps we need a new frame of mind to think about the future of work altogether. How do we flip the script on the conventional human-versus-machine narrative?

Dystopian scenarios, as some writers have observed, don’t factor in benefits such as ways technology can be used by workers to collaborate, make better decisions, be liberated from drudgery, or collectively harness intelligence in ways making work more productive and meaningful — and possibly without need for a management team at all.

Virtual reality, robots, and artificial intelligence are no longer fantasies from a distant future. They are with us today and will become increasingly common. As these elements advance into everyday use, however, they raise the question: how will they transform the economy and society? If companies, thanks to automation, AI, or robotics, need fewer workers, what happens to those who once held those jobs and may lack the skills for new ones? And since presently many social benefits are delivered through jobs, how will people outside the workforce for extended periods receive health care or other needed benefits?

Mariko Mori, Entropy of Love, 1998. Courtesy of Deitch Projects

Interestingly, new models are emerging. According to author David Passiak, when thinking about the future of work, we need to highlight the power of blockchain. This technology is on the cusp of enabling us to track of our economic contributions at a granular level and potentially compensating directly for labor or contributions to the common good.

At this point, we should say that we don’t mean to sound like techno-utopians. We are simply interested in proposing another viewpoint to counter dire predictions of gloom. At the same time, we don’t mean to be cheerily oblivious to looming dangers. For example, all the data-heavy innovations coming down the pike consume an enormous amount of energy, potentially further exacerbating the climate crisis we are in, and endangering resources. Hopefully, means will be developed to grapple with these challenges, as many of these developments that have appeared quite recently over the horizon will potentially create a new horizonality of opportunity and free us up in hitherto unimagined ways.

Central are the power and promise of DAOs — decentralized autonomous organizations. The original DAO was an organization created by developers to automate decisions and facilitate cryptocurrency transactions. And this was made possible by the blockchain — as you may know, a kind of digital ledger that exists in the “cloud,” having the potential to record an infinity of transactions — indelibly. If I make a pledge to transfer to you certain goods, this can be recorded and referenced in the blockchain — with no need of banks or brokers or traditional mechanisms of recording such exchanges. Blockchain makes cryptocurrency possible, but — and here is its revolutionary potential — it also enables limitless other transactions, organizing exchanges between individuals, operating in a potentially decentralized way, outside any bank or government or other traditional structure.

It is an eco-system if you will, that operates on its own, represented by rules encoded as a computer program. Thus, in theory, it is a kind of collective wisdom: the best ideas can bubble up through a process of co-creation between “team” members, rather than through a top-down hierarchical leadership structure; people mutually support each other managing projects. Likewise, DAOs, based on blockchain, have the principles of collaboration and collective decision-making at their core.

Importantly, this creates a new horizontality that potentially removes the role of the “middle-man” or broker in transactions, and takes power away from authorities and puts it in the hands of individuals. All this falls under the umbrella of Decentralized Finance, or DeFi — as do the currently hot-topic NFTs (Non Fungible Tokens, a digital record of visual phenomenon), Ethereum (a cryptocurrency that is also a non-hackable financial platform), and smart contracts. These provide a set of tools and protocols that offer a remarkable alternative to our current financial system.

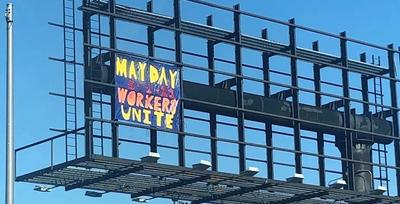

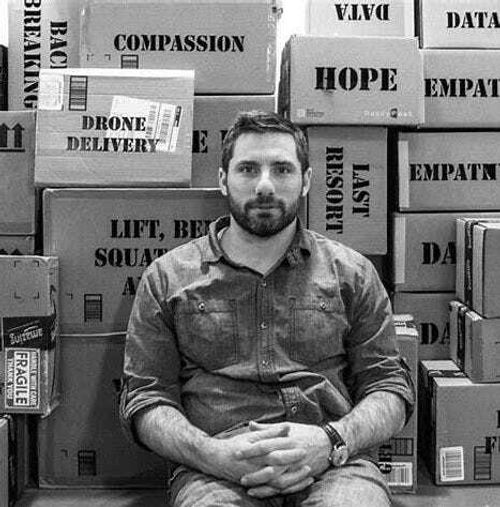

Brett Wallace, The Future For Workers, installation view, Maryland Institute College of Art, 2019. Photo: Dan Meyers

In the last decade, the term “disruption” has become a well-trodden catchphrase, usually indicating millennial buccaneer venture capitalists noisily bringing about the kind of shocks to the system supposedly necessary for innovation. The blockchain, NFT’s, the DAO, are certainly “disrupters” of traditional financial procedures.

Yet the true “disrupter” has been Covid-19, making us question and redefine our very physical environment — notably, the office. All the metaphors for doing business and sealing a deal — the handshake, the backslap, the face-to-face meeting — have transmogrified into life-threatening actions. This true “disruption” has pushed us abruptly in a direction toward which we were inching our way anyway, arriving now with a bang. Remote work has thrown offices and personal lives into turmoil and brought heightened cybersecurity concerns to bear. Yet this virtual universe also offers a new globality, increased flexibility; it has shattered traditional business hours and brought about a combination of personal and professional life previously available only to those at the top of the pyramid. It is also creating entirely new job descriptions and sectors of work.

As we return from the remote, isolated, virtual reality in which we’ve been living over the past year, how will this affect the nine-to-five work-world? Many pundits have predicted the end of the office, of the city — yet much is yet to be understood.

Through new technologies, we wonder whether there might even be the possibility of a new egalitarian exchange? Perhaps from technology’s efficiency and enhanced capability, it is conceivable that we can, as a society, create wealth and then, employing approaches such as Universal Basic Income, distribute it equally. (For those resistant to the prospect of UBI’s apparent offer of “free money,” the initiative is more complex than it seems and worth exploring.) Along the same lines, while we think of automation as wreaking unemployment, it may also potentially remove the need for the kind of heinous, low-paying jobs that are so dehumanizing — picking fruit in the hot sun or cleaning toilets. Indeed, political scientist and cultural observer Darrell M. West argues that we need to rethink the concept of jobs entirely, to reconfigure the social contract, to move toward a system of lifetime learning, and to develop a new approach to politics.

We still operate largely inspired by nineteenth- and twentieth-century models based on hierarchies and adversarial zero-sum calculations (boss vs. worker/rich vs. poor). But vast cultural shifts are happening, changing the way we think about race, equity, privilege, wealth, whiteness — and how these impact our work lives.

Perhaps the day might come, for example, we may no longer be enslaved to a “job” and work-for-pay would be contextualized within a larger social compact in which many of the basic human needs (shelter, food, healthcare, etc.) are met through other means, such as universal basic income, for example. And thus, elements of work beyond making a living wage might be foregrounded: acts of service, creative, physical, and intellectual satisfaction. Yes, it sounds utopian, but it is possible that all human occupation might be evaluated and rewarded in new ways — for example measuring the degree to which it contributes to the social good. In this way, Blockchain and other technologies usher in a kind of pragmatic utopianism.

Yet, how can we truly ensure full opportunity for all and redress past wrongs? Aspiring toward a more level playing field, how do we grapple with the reality that those with power are reluctant to relinquish it? The internet may be the future — but many still do not have access to high-speed internet. Those who have suffered at the hands of history may not be overly optimistic that things will suddenly, systemically transform, having seen all too often that, despite fine words, power remains in the hands of the privileged.

Nonetheless, new tools, albeit slowly, are emerging to ensure true diversity in the workplace as well as on the upper rungs of the economic ladder. For our own good, we have to work hard to overcome obstacles to equity. Yet, certainly, we will experience periods of backlash and regression - most of all in our offices and professions.

If we can set our sights thirty years out, we can dream ideal conditions that at this moment seem hard to conceive but are nonetheless not impossible: a truly equitable work environment, endlessly creative and productive, not eschewing conflict or risk, but enticing us all to move ever forward.

Stranger things have happened. Who knows what the future holds?

—Yona Backer, Visions2030 Executive Director, and Carey Lovelace, Founder

Cleaning Conditions, Suzanne Lacy with Meg Parnell, Manchester Art Gallery, 2013

Beginning in front of Work, a painting by Ford Madox Brown in the Pre-Raphaelite Gallery, teams of “sweepers” from labor and immigration organizations cleaned the galleries each day and redistributed a very visible “litter” of political printed materials onto the floors. After the cleaning, questions on the intersection of immigration, labor, living wage and the role of women in the care and service industries were raised through a series of conversations that included activists, politicians, students and the public. In addition, the Manchester Gallery staff gathered in private cross-sector conversations on their own work and its relationship to the global gendering of care and service.

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT:

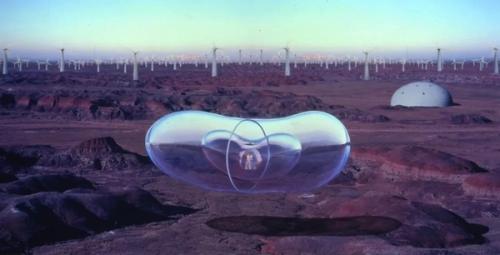

Brett Wallace (American, b. 1977 in Boston, MA. Lives and works in New York City) is a conceptual artist and entrepreneur whose art practice, through video, narrative storytelling and installation, explores the labor model and territories within accelerated capitalism.

His Amazing Industries: Floating Factories, for example, has a dystopian edge, exploring the archetype of a mega-corporation encroaching on our daily lives; it also offers a glimpse of a kind of futurescape.

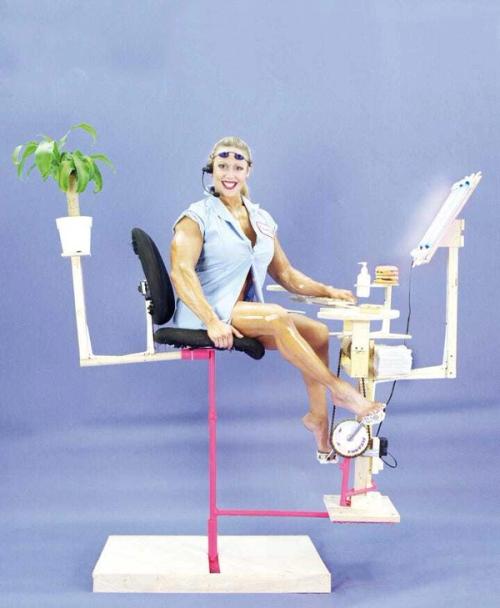

Mikka Rottenberg, The cardio solaric cyclopad-work from home as you get fit and tan, 2004. Courtesy Nicole Klagsbrun, New York.

Saya Woofalk, Virtual Chimeric Space, 2015