Leonardo Da Vinci imagined flying machines and the submarine. Nineteenth-century painter Samuel Morse (a distant relative of mine) invented the telegraph. The intersection of art and invention is long-standing; the key is the imagination. It can create great paintings – and construct new worlds.

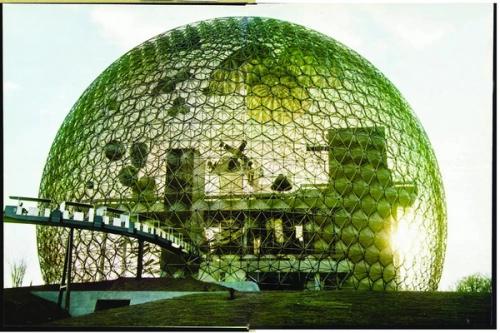

(Courtesy of The Buckminster Fuller Institute)

2020Visions is committed to opening up horizons – knowing that inspiration can untangle barriers of habit. From our minds, we create pictures of the world. Science, like art, is a model to help us understand our lived experience.

Particularly in the 20th century, when it began to free itself of the picture frame and the pedestal, art began to interact directly with the world of “lived” life — initially, the industrialized world, embracing new materials and capturing a novel ethos. In 1909, the Futurists in Italy celebrated technology and speed at a time when the automobile was still a novelty. In Russia, artist Vladimir Tatlin's never-built 1919-20 Constructivist tower, a leaning iron-glass-and-steel twin helix, was a symbol of modernity, meant to spiral up almost a quarter-mile in height, different portions making complete rotations in the course of a day, a month, a year. A projector at the top would cast messages across the clouds.

Guglielmo Tato Sansoni, "Airplanes Dive Over Enemy Skies" (Italian Futurism Futurist Transportation Plane), 1930s

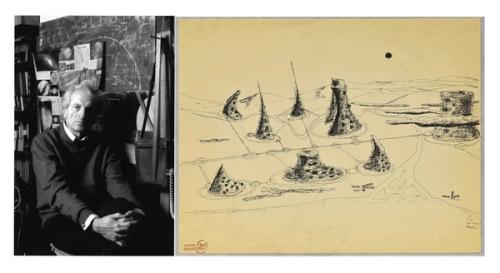

Vanguard artists were intoxicated with the future. Some turned their skills to idealistic solutions for global problems. Greek-born avant-garde composer Iannis Xenakis (trained as an engineer, having worked with Le Corbusier) in the early 1960s minutely planned a 3-mile-high vertical Cosmic City that would preserve the countryside by occupying a very small footprint. Among other features, permeable walls would let sunlight in. In late 1960s New York, artist Robert Rauschenberg and engineer Bill Klüver, among others, founded Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), promoting collaborations between artists and engineers. They implemented real initiatives, such as satellite broadcasting instructional programs into remote parts of India. Or Telex: Q&A (1971) an event where — the erstwhile hi-tech telex — linked public spaces in New York, India, Tokyo, and Stockholm, allowing people from different countries to question one another about the future.

Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001), pictured next to his Cosmic City (aerial perspective), 1963, ink on paper, 8 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches (Courtesy Iannis Xenakis Archives, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris). An unrealized urban plan for 5 million inhabitants, where wide-open green space is punctuated by fantastical, organic towers spiraling into the sky, bringing the dwellers “into the proximity of the stars.”

I encountered this kind of work as a student in the 1970s, confused yet inspired by its impossible ambitions. Awash with big dreams and Grand Experiments, that era (possibly fertilized by logic-shattering LSD) reimagined society in fundamental ways. Sometimes, the work had charming, absurdist humor. Mierle Ukeles, before becoming artist-in-residence to the New York City Department of Sanitation, in 1969, wrote a Manifesto for Maintenance Art – dividing the world into “creating” and “maintaining.” Her piece Touch Sanitation (1979-1980) involved the artist personally shaking the hand of every garbage-worker in the city. I worked for a while with Bonnie Sherk, who had created Crossroads Community (the farm) (1974-1980), a working farm beneath a San Francisco underpass, where animals, crops, children, and artists co-existed.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles in her Touch Sanitation Performance from 1979-80. (Credit: Robin Holland/Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts)

Some of this holism was influenced by the Women’s Movement, which conceived a non-patriarchal, non-hierarchical world where all voices could be heard. (One of my favorite pieces: the Los Angeles-based Feminist Art Workers’ 1978 telephone performance This Ain’t No Heavy Breathing. Instead of obscene phone calls, they whispered messages of empowerment.) But this solution-oriented work was also inspired by German artist Joseph Beuys’ “social sculpture,” with its vision of healing society. A co-founder of the Green Party, Beuys created works such as 7,000 Oaks (1982), which involved planting just that number of trees throughout Kassel, Germany – the work intended to signal the possibility of shaping the physical urban environment. In his Direct Democracy, instead of voting for elites in parliament, people were to vote directly on issues affecting them.

“I believe that planting these oaks is necessary not only in biospheric terms, that is to say, in the context of matter and ecology, but in that it will raise ecological consciousness – raise it increasingly, in the course of the years to come, because we shall never stop planting.” — Joseph Beuys

Spotlight: Pioneers of Social Dreaming

JUDY BACA: VISIONARY MURALIST

(L): Judy Baca with her mural-painting team. (R): A representative from SPARC, cleans a portion of Baca's "Great Wall of Los Angeles" “Sojourners (Chinese immigrants) 1848. (Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

Some artists attempt impossible tasks, some map out alternative pathways. Judy Baca has done both. Raised in the LA barrios, Baca, enlisting over time some 400 community youth, including gang members and incarcerated youth, created the quarter-mile-long mural The Great Wall of Los Angeles (1975-present), on the concrete sides of the Tujunga Wash, part of the drainage system of Los Angeles, California. The mural, 13 feet high, painted directly on concrete is 2,754 feet long and covers 6 city blocks; one of the longest murals in the world. Baca offered her teams of mural painters new skills and community as they articulated “hidden histories” in the building of the California Southland, stories of Native peoples, Latinos, Chinese immigrants, citrus pickers, women — stories never told.

At 2020Visions, we like to point out creative minds who have forged ingenious solutions. The idea of alternative histories and community engagement that Baca pioneered at the time was uncommon — but no longer. The recently retired UCLA professor has remained active with ever more engaged community projects, as well as running SPARC, the Social and Public Art Resource Center, headquartered in Venice, California.

Foundational Inspiration

R. BUCKMINSTER FULLER: “DESIGN SCIENTIST”

Buckminster Fuller with his Dymaxion Car and Fly’s Eye Dome, 1980. (Credit: Roger Stoller)

20th-century design in particular promoted forward-thinking practices. In Holland, abstract art movement De Stijl aimed to achieve visual harmony to pave the way for utopia by removing the individuality of the artist. The Bauhaus strove to humanize industrial innovation, combine aesthetics with everyday function, mass production with individual expression.

Architecting the Future

Visionary Buckminster Fuller, an originator of the geodesic dome, defined himself as a “design scientist” – an emerging synthesis of artist, inventor, mechanic, objective economist, and evolutionary strategist. In 1949, for example, Fuller erected his first dome, made from aluminum aircraft tubing with vinyl-plastic skin, its form an icosahedron. To prove the tensile strength of his apparently fragile design, Fuller himself suspended from the frame of the structure.

In Architecting the Future, Elizabeth Thompson, 2020Visions consultant, and former director, Buckminster Fuller Institute, writes about the iconoclastic architect’s view of how to shape our trajectory as a civilization.

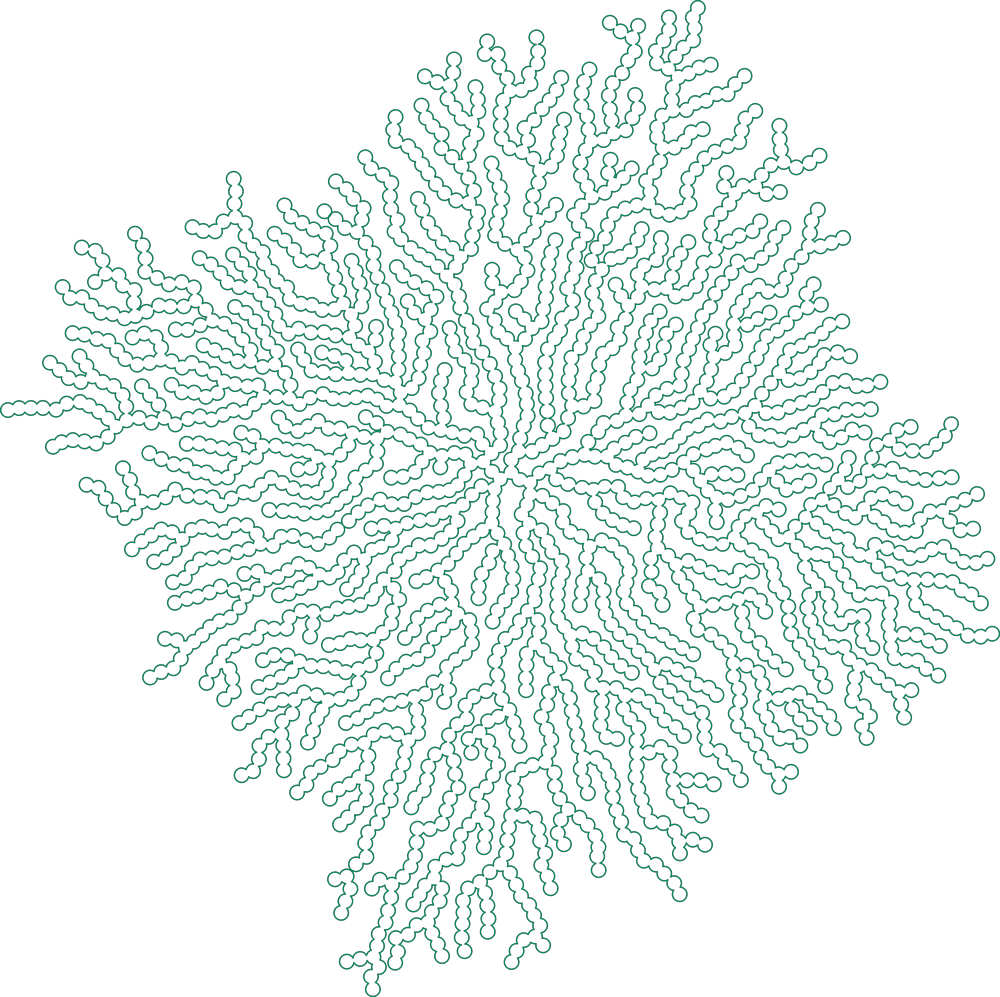

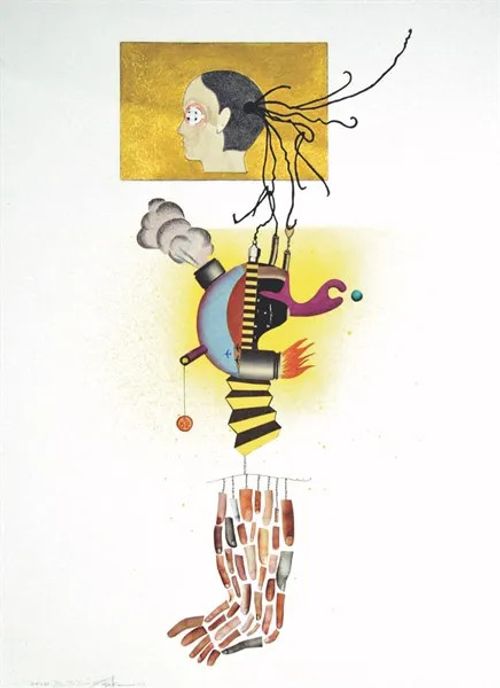

Exquisite Corpse. A collective drawing in which each collaborator adds to a composition in sequence, being allowed to see only the end of what the previous person contributes — until the conclusion. It shows how illogical combinations can spark ingenious forms. (source unknown)