The Future of Past,

…the Past of the Future (Part II)

In the anarchic, idealistic late 1960s—when we had cured polio and just landed on the Moon—sky, water, and the forest seemed endless. Suddenly, books like The Greening of America and The Silent Spring alerted us to a possible disaster. But given past technological success, it promised to lie within our powers to overcome deforestation and the decimation of species. It was simply a matter of becoming aware.

Through the mid-1960s, High Art existed in its own exalted, formalist sphere, aspiring after a state of purity. But with the counterculture, newly-activist artists descended from ivory towers—first, to protest the Vietnam War, and found themselves at the forefront of many battles. Why not ecology? In 1968, Argentinian artist Nicolás García Uriburu, colored Venice’s Grand Canal with a (harmless) fluorescent green dye to dramatize civilization’s fragile relationship to nature. Perhaps art itself could change the world, raise consciousness? The possibilities were bracing and exciting.

Nicolás García Uriburu, Coloration of the Grand Canal of Venice, 1968. © Fundación García Uriburu

Back to the Earth

This was a moment when artists began to see that their work, while remaining “art,” could have other sorts of powerful effects. Art was expanding outside of the gallery and studio. Land Artists were exercising their imagination—and engineering prowess—in sculptural acts executed on vast territories. Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, a 1,500-foot long coil, winds counterclockwise off the shore of the Great Salt Lake. Michael Heizer’s Double Negative involves two long straight trenches, 30 feet wide, 50 feet deep, cut into the desert sandstone “tabletop.” While these works had no particular social purpose, they demonstrated that the “frame” around art could be extended infinitely.

Herbert Bayer, Mill Creek Canyon Earthworks, 1982. Photo: John Hoge

But it began to occur to artists that while moving earth, they could heal it. Smithson, for one, fought hard for despoilers of lands to let him remodel their industrial devastating. Beyond enlightening or illustrating, or even “raising consciousness,” as Uriburu’s Venice canal piece did, art might engage systemically, radically, and fundamentally.

Spotlight: Mel Chin

L: Mel Chin's Revival Field, 1991, Pig's Eye Landfill, near St. Paul, Minnesota. Courtesy of Walker Art Center Library and Archives.

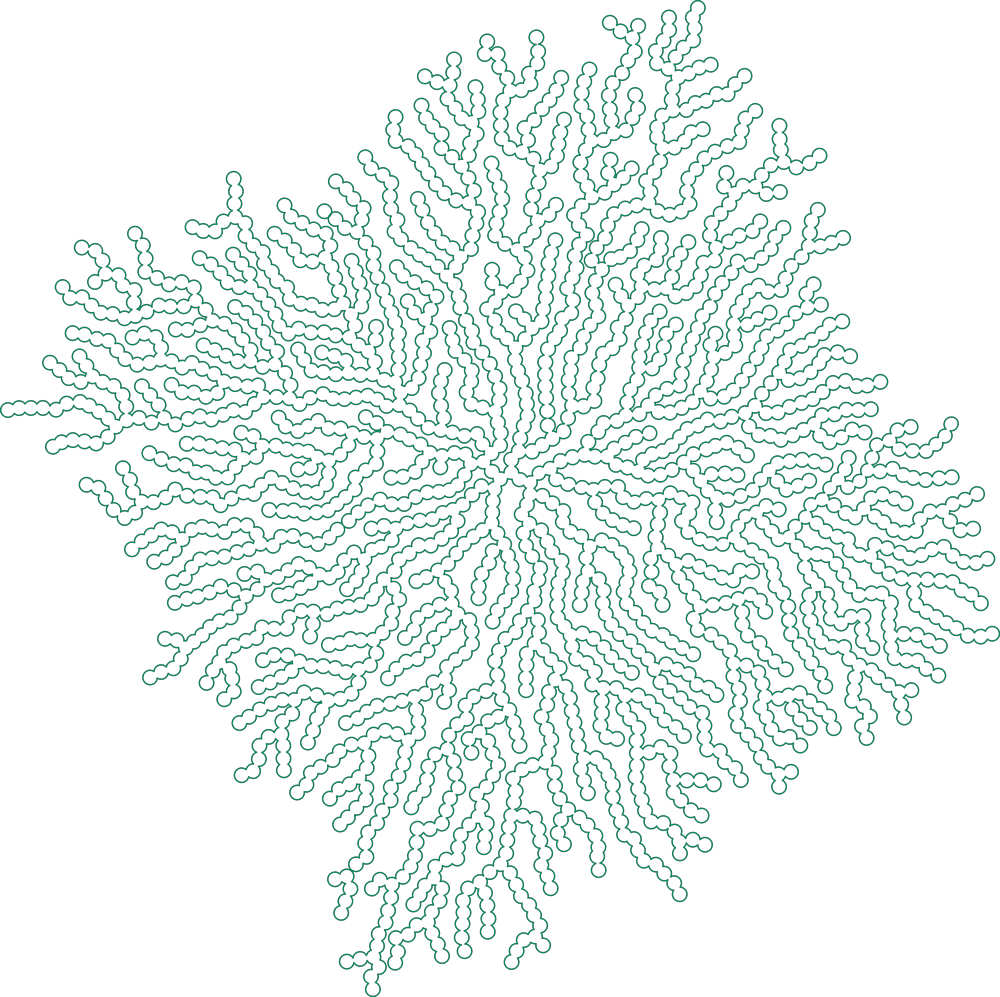

Late in the 1980s, conceptual artist Mel Chin came upon an article about phytoremediation of toxic land (using plants as remediation agents) written by an expert in psilocybin. Chin had an epiphany: “The future sculpture is plants!” He began what would become Revival Field, containing the intent to sculpt a site’s ecology, joining forces with USDA senior research scientist Dr. Rufus Chaney. Together, they sought out hyperaccumulators—plants that have evolved the capacity to selectively absorb and contain heavy metals from contaminated soil into their vascular structure. Scientific analysis of biomass samples from Chin’s field confirmed the potential of “green remediation” as an on-site, low-tech alternative to current costly and unsatisfactory remediation methods. Controversial in the arts-funding community—who questioned whether it was art at all—the project, located at Pig’s Eye Landfill in St. Paul, Minnesota, a State Superfund site, is ongoing, comprising of plants and industrial fencing on a hazardous waste landfill.

If that [pollution] could be carved away, and life could return to that soil… then that is a wonderful sculpture… But we have to create the chisels, and we have to create the tools, and we have to isolate the problem: where the block of pollution is, so we can carve it away… I just needed to take the poetry of this idea and turn it responsibly and pragmatically into reality.

—Mel Chin

Spotlight: Rick Lowe

Rick Lowe has helped revitalize Third Ward through his Project Row Houses "social sculpture." Photo: Brett Coomer, Staff / © 2014 Houston Chronicle

Houston-based artist Rick Lowe actively defines himself as making “social sculpture;” Project Row Houses are considered a key example of social-practice art. Along with artists David Chung, James Bettison, Bert Long, Jesse Lott, Floyd Newsum, Bert Samples, George Smith and community organizers, Lowe arranged for the "purchase and restoration of a block and a half of derelict properties—22 “shotgun” houses from the 1930s—in Houston's predominantly African American Third Ward. These houses, converted to art spaces, serve as a community platform to enrich the lives of Third Ward residents and the wider Houston community, with an emphasis on art and cultural identity within the urban landscape. More than 20 years later, according to an ArtNews article, the project has grown to 49 buildings spread out over 10 blocks and has a support program for young mothers.

Keep Reading: Rick Lowe: Project Row Houses at 20

Collaboration...is essential to Eco-art.

Nancy Holt, Sky Mound (1984-), Hackensack Meadowlands, New Jersey, Unrealized earthwork, © Holt/Smithson Foundation, licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York

Partnerships not only create something more than the sum of their parts but crack fixed categories open. Indeed, Eco-art can be seen as collaborating with the earth itself.

As seen in the works of the Harrisons, Johanson, Bayer, Holt, Miss, Rahmani, Chin, Lowe, Gellis, and Labowitz, kernels of ideas can’t take form without the help of others: landscape architects, engineers, civic agencies, agronomists, scientists, and volunteers.

Architects, for one, are accustomed to joint endeavors (albeit usually operating often under the rubric of a lead designer). However, the Western art tradition celebrates the “hero artist”—the genius at the pinnacle of a hierarchy. Collaborative work, multiple authors sharing equal prominence, was little valued and almost unheard of—until the Women’s Movement of the 1970s.

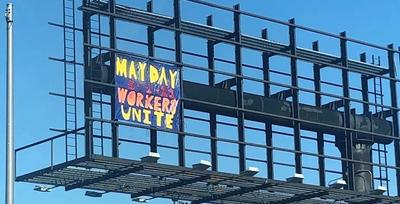

Starting with the pioneering Redstockings of 1968, the Ad Hoc Committee of Women Artists in 1970, and Judy Chicago’s “Fresno Feminist Art Program,” feminism championed group efforts and collective artworks, questioning individual authorship.

Coincidentally, many key figures in Eco-art have been leading art feminists: Leslie Labowitz (Sproutime), Aviva Rahmani (Ghost Nets), Mary Miss (South Cove) were all leading figures in the Women’s Movement in art. Helen Harrison’s first artwork was a performance at the Los Angeles Woman’s Building. (And Mierle Ukeles, Artist-in-Residence for the New York City Department of Sanitation, whose Touch Sanitation was discussed in an earlier Newsletter, developed her ideas about “maintenance art” from a feminist appreciation that women have been relegated to “maintaining” rather than “creating.”)

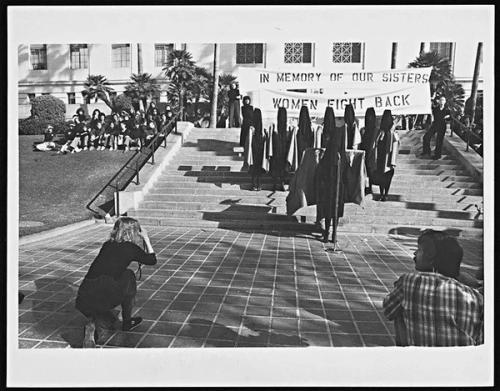

In particular, Sproutime’s Labowitz in the late 1970s collaborated with pioneering feminist Suzanne Lacy, responsible for two landmark epic communal performance works, In Mourning and In Rage and Three Weeks in May, the first large-scale public protests ever against sexual violence toward women—a remarkable hybrid of performance and activism. They brought together not only multiple artworks around Los Angeles (and anthems by folk singer Holly Near), but also partnerships with civic agencies, local government officials, rape crisis hotlines, and self-defense centers.

2020Visions is dedicated to creating new models and paradigms of society. While these activist works about rape are critiques, exposing painful realities, they also offer startling new models of collaboration—not just across disciplines, but genres and mind-sets.

In Mourning and In Rage media performance at Los Angeles City Hall, December 13, 1977, Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz-Starus. The Getty Research Institute, Lawrence Alloway Papers, 2003.M.46. Photo courtesy of Susan Mogul

What’s one thing can you do today to help change our planet for the better?… Use your imagination.

To Prime the Imagination: Morning Pages…

….are three pages of longhand, stream of consciousness writing, done first thing in the morning. *There is no wrong way to do Morning Pages*–they are not high art. They are not even “writing.” They are about anything and everything that crosses your mind–and they are for your eyes only. Morning Pages provoke, clarify, comfort, cajole, prioritize, and synchronize the day at hand. Do not over-think Morning Pages: just put three pages of anything on the page... and then do three more pages tomorrow.

— Julia Cameron, The Artists Way

Farid Belkahia, Hand (main), 1981. Dye and henna on vellum laid on board, in nine parts 152 by 130cm.; 59 7/8 by 51 1/4 in.

For Further Study:

A list of books about early ecological Land Art, artists, and projects through 1992.