“When day comes, we step out of the shade aflame and unafraid. The new dawn blooms as we free it. For there is always light. If only we’re brave enough to see it. If only we’re brave enough to be it.”

— Amanda Gorman

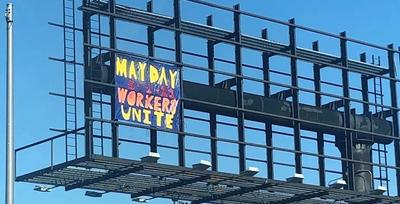

As I listened to Amanda Gorman recite “The Hill We Climb” on Inauguration Day, I returned to the idea of hinterlands. Gorman, the youngest Inaugural poet and first person to be named National Youth Poet Laureate, spoke of dreaming of becoming president and of how this moment in American history makes that dream even more real and even more perceptible.

A hinterland is an area beyond a city or district; by definition, it is always beyond the visible. When considering Black Diasporic experiences in America, it can feel like this—a place where we go unseen or feel seen only within our constructed communities. I’ve long been interested in this concept of being or existing beyond the visible and in visualizing that experience for myself and others. In my long-term photographic series “Jewels from the Hinterland,” people and places become sites that exist beyond mainstream depictions of Blackness; a photograph creates an alternative present by reclaiming urban green spaces as places of tenderness, beauty, and play for people of the African Diaspora. The photograph becomes a tool to assert and insert our presence in these landscapes, to create glitches and holes within preexisting frameworks of urban decay.

When I think about the expansiveness of Afrofuturism, something of which we’ll only scratch the surface in this newsletter, I think about the beauty and challenges of self-recognition. Afrofuturism creates a home for people who exist outside, around, and beyond the mainstream to foreground sci-fi, technoculture, magic, and fantasy. The ideas are not new, despite the fact that the term was coined by culture critic Mark Dery in 1994. They existed long before and, at their core, highlight and activate an emergent and ever-changing freedom.

It is in this freedom—this ability to architect one’s future, one’s community, one’s framework for existence—and in the necessity of dreaming that we’ll situate ourselves here, with contributions from architect Vanessa Keith, principal of StudioTEKA, an award-winning design firm she founded in 2003; Black Magic, an Afrofuturism book club; an encore of our New City conference conversation with Black Futures authors Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham; and a resource guide for supporting New York–based Black women farmers and herbalists. We hope this newsletter creates points of entry and expansion as we start this new year.

Readers, this will be my final newsletter as editor-in-chief after a year of striking shifts and adaptations. I look forward that for all that is to come for 2020Visions, including a new name!

With gratitude,

Naima Green, Editor-in-Chief, 2020Visions

Spotlight: Vanessa Keith

Still from Johannesburg market rendering, 2021 ©StudioTEKA

We first hosted Vanessa last December at our virtual three-day The New City: Navigating the Future, a How-To, where, with architect Matthijs Bouw, she spoke about future cities and sustainability. We sat down with her again to talk about Afrofuturism and what it means to be an architect who considers every surface of an environment as a potential site for design intervention. The animations below feature two brand new StudioTEKA projects born from Keith’s book 2100: A Dystopian Utopia: The City After Climate Change. (Purchase the book or e-book.) As the book imaginatively projects:

Fast-forward to the year 2100. New York—along with Phoenix, Beijing, São Paulo, Manila, and many more of the world’s most populated cities—is irrevocably changed. Much of the earth’s great middle swath is subject to droughts, wildfires, and desertification, while increasingly frequent superstorms plague coastal areas, destroying precious agricultural lands by bringing seawater far inland. Where in the world shall we live, and what will our built environments be like? How can we change our way of life to be more in keeping with natural systems and processes? In 2100: A Dystopian Utopia, Vanessa Keith and StudioTEKA visualize possible design solutions to suggest the profound adaptability of and possibilities within the design field to meet environmental challenges of the future. The issue is framed by noted sociologist Saskia Sassen in her preface to the book advocating “delegating back to the environment.”

Listen: Vanessa Keith and Naima Green in Conversation

“We're talking about Afrofuturism, or Indigenous futurism from Indigenous or local knowledge, African-based knowledge, and diaspora-based knowledge. There are a lot of things that have been preserved, thankfully; but that have been ignored as ‘Oh, well, that's primitive, or that's bush medicine, and I want to go to the pharmacy and get a plastic bottle with pills in it instead of the bush medicine.’ We're actually realizing now that a lot of that is wrong, and that we actually do have a lot to contribute.”

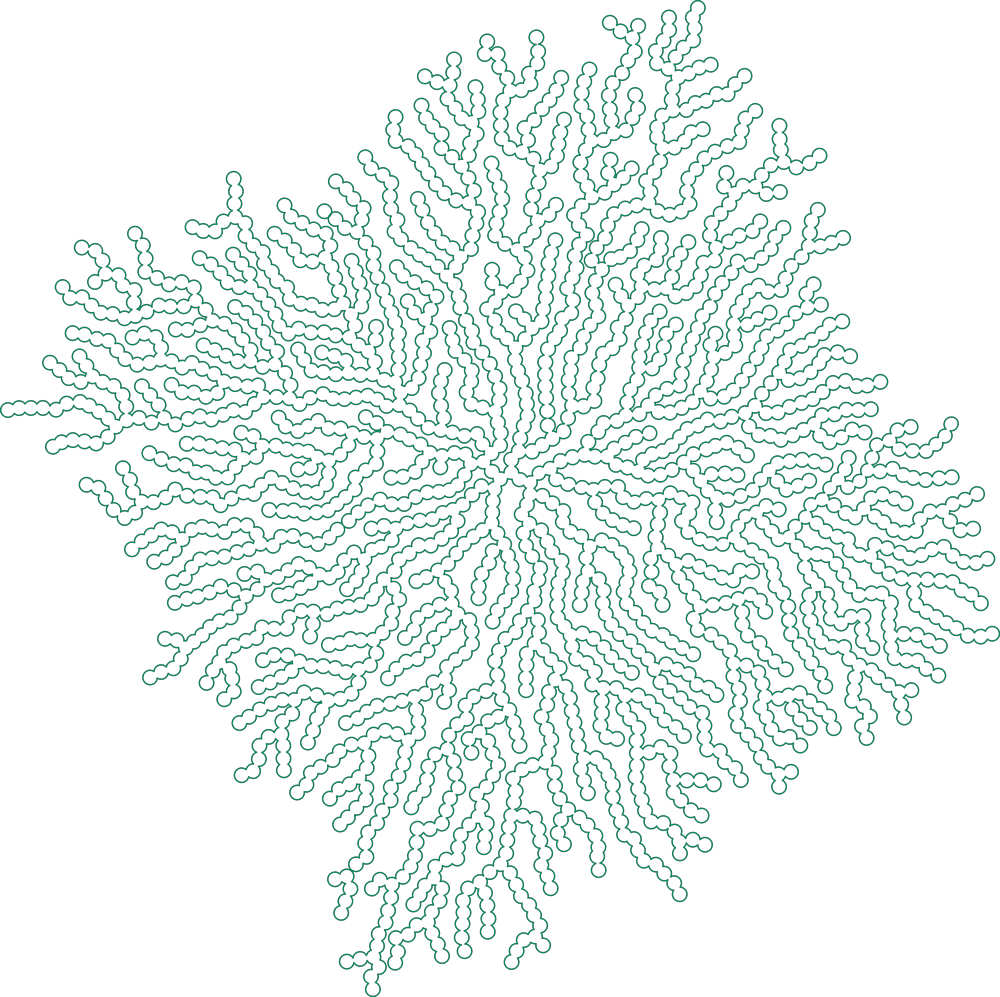

Below, StudioTEKA shares freshly created solutions-based animations of what two cities, Johannesburg, South Africa, and São Paulo, Brazil, could be like in the future. These renderings are expanded views originating from 2100: A Dystopian Utopia: The City After Climate Change.

Afrofuturism and Indigenous Futurism offer powerful alternatives to a dominant global paradigm rooted in the plunder and exploitation of the Earth’s resources into a linear system of production. Here, by positing humanity as but one of many layers form part of a larger interdependent system, we can function as a loop rather than a line. The São Paulo settlement is envisioned as both communal and interconnected. Cooperative farming and community-supported regenerative agriculture link our bodies to the earth in a profound way. People sleep in pods suspended above the land that nurtures them. Elevated pathways allow for circulation in both rainy and dry seasons, while flexible agriculture plots, held in place by vertical guidance posts, allow planting beds to float, thus preserving precious food production during storms. The system of connected bikeways and pedestrian paths is suspended over repurposed buildings, communal facilities, rainforest timber farms and agro-food forestry, aquaponics installations, fish farms, and medicinal-crop fields. These are thought-provoking eco-futurist alternatives to the ways we currently live, extract, manufacture, and consume food and energy in 2021. We use ancient, time-honored strategies based on preserving nature and on natural methods to sustain human inhabitation. Localizing the network of exchange allows community agency and autonomy and promotes a thriving relationship between humanity and all other beings that inhabit the planet with us.

Black Magic . . .

…is an Afrofuturism Book Club, a collective of magical, radical dreamers, with a space to envision, imagine, and co-create other possible futures.* Since our founding in 2014, together we have studied over 20 Afrofuturism titles, including books, short stories, essays, films, and comics. In 2019, we hosted a community dinner and conversation at Creative Time’s Summit X titled “Sowing Seeds for Survival: Lauren Olamina & the Truth about the End of the World in Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower.” In 2020, BLACK MAGIC also facilitated “Parable Lessons,” a virtual conversation about the important teachings from Octavia E. Butler’s Parable Series at the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Art (MoCADA). Currently, we are preparing to launch a virtual book club, while also developing Parable School, a community skill-sharing academy for the apocalypses that may come.

BOOK LIST

- Midnight Robber, Nalo Hopkinson

- Parable Series, Octavia E. Butler

- Bloodchild and Other Stories, Octavia E. Butler

- Lilith’s Brood: The Complete Xenogensis Trilogy, Octavia E. Butler

- Patternist Series, Octavia E. Butler

- The Truth About Awiti, CP Patrick

- Who Fears Death, Nnedi Okorafor

- Akata Witch, Nnedi Okorafor

- I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem, Maryse Condé

- Recurrence Plot and Other Time Travel Tales, Rasheedah Phillips

- A Pure Solar World: Sun Ra and the Birth of Afrofuturism, Paul Youngquist

- Filter House, Nisi Shawl

- Kindred: A Graphic Novel Adaptation, Octavia E. Butler, Damian Duffy, and John Jennings

- The Inheritance Trilogy, N. K. Jemisin

- Children of Blood and Bone, Tomi Adeyemi

- Mindscape, Andrea Hairston

- Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora, edited by Sheree Renée Thomas

BLACK MAGIC Leadership Team

Suhaly Bautista-Carolina, Makeda Farley, Yisa Fermin, Janis Irish, Tanya Diallo Koshar, Elizabeth Rossi, Megan Williams

Instagram | @weareblackmagicbookclub; E-mail | blackmagicbookclub@gmail.com

Special thanks to BLACK MAGIC collaborators: Ana María Agüero Jahannes of VibeisBright, Stephanie Alvarado of Fotos y Recuerdos, WordUp Community Bookstore/Libreria Comunitaria

We love to support Black-owned bookstores; here is a list of 125 across the US.

Black Futures: The Book, the Talk

Brooklyn-based writers and curators (and friends) Jenna Wortham and Kimberly Drew coedited Black Futures, a collection of essays, memes, dialogues, recipes, tweets, poetry, and more—to tell the story of the radical, imaginative, provocative, and gorgeous world that Black creators are bringing forth today.

Honoring Ancestors, Land, and Community Care

Among the silver linings of 2020 were the beautiful expressions of mutual aid. Communities came together in a multitude of ways. Herbalists like Moon Mother Apothecary, Sacred Vibes Apothecary, Goldfeather, and Augustine Herbals prepared medicine for people marching in protests, those dealing with immense grief and in need of rest, lifting some of the weight off of us experiencing great loss.

Two farmers, Leah Penniman and Amber Tamm, shine as activists who deeply advocate for access to food. Penniman founded the Afro-Indigenous-centered community Soul Fire Farm (Petersburg, NY), which is “committed to uprooting racism and seeding sovereignty in the food system. We raise and distribute life-giving food as a means to end food apartheid. With deep reverence for the land and wisdom of our ancestors, we work to reclaim our collective right to belong to the earth and to have agency in the food system.” You can also read Penniman’s book Farming While Black.

Amber Tamm is a farmer who spent most of her career growing on other people’s land. She started the Future Farm Fund to build a farm that will belong not just to her, but to the communities around her and those in need of access to food. I met Amber over the summer of 2020 near the former site of historic Seneca Village in Central Park. She proposes dedicating a portion of the land to a seed garden in memory of the 19th-century land-owning Black residents of Seneca Village and the indigenous Lenape people, and also launching a farmer-training program for young people between the ages of 16 and 20.

Cauleen Smith, Sojourner, 2018. 22 minutes and 41 seconds

“Afrofuturism, for me, is about speculating on the potentiality of what is known about technology and physics to create metaphors that allow me to explore an African diasporic past and generate possible narratives for the future.”

— Cauleen Smith, 2011

"Designing from an Afrofuturistic standpoint means centering perspectives that have been too often overlooked and that provide a dynamic way forward for us all in tackling the climate crisis. This wisdom is at the same time ancient and innovative and is firmly grounded in traditional approaches that value hybridity, fluidity, and adaptability. 2100 Johannesburg shows an elevated settlement containing buildings and infrastructure that are hybrid both in use and organization. This vibrant and activated site contains residential, commercial, and recreational spaces, as well as renewable energy generation, green transportation, and urban farming and permaculture. In this eco-futurist projection, the built environment has become one with its surrounding natural context, and the buildings themselves have become an inviting habitat for plants and weaver birds, buzzing and humming, full of life. Energy, food, and local culture are integrally connected to the landscape, while the market serves as a hub for local cultural events and spontaneous happenings. By combining time-honored practices and local wisdom with emerging technologies and techniques, we construct a dynamic Afrofuturistic envisioning for this city of millions."