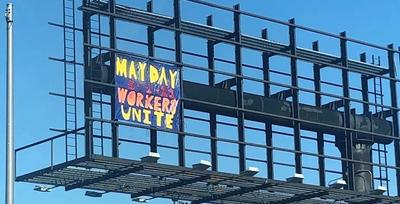

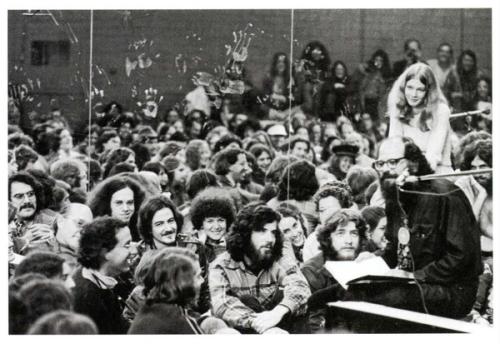

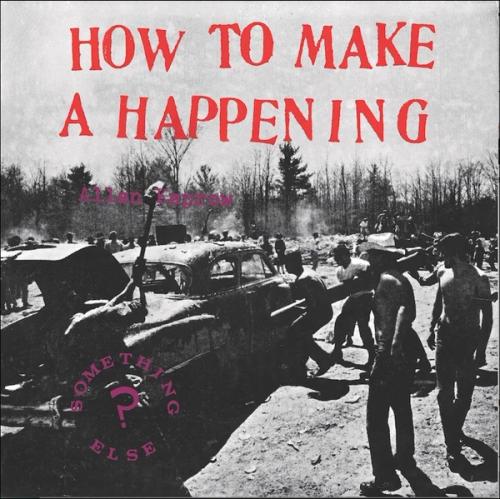

Hippies erected a Buckminster Fuller Geodesic Dome in the courtyard. Long-haired faculty from the fringes of the avant-garde signed memos, “I embrace you!” There were classes in “alternate states of consciousness” and, rather than grades, experience reports that could be a poem or even a pot. Alan Ginsberg floated through in white robes, playing his sruti box, wrapped in the scent of marijuana; Allan Kaprow organized Happenings where an ice cube was passed mouth to mouth; Ravi Shankar played sitar in the Burbank quad of the decommissioned Catholic girls’ school, the school’s first home.

Author pictured upper right – CalArts, 1971. Photo: Tom Fiorelli; © California Institute of the Arts Archives

It was 1970, and the counterculture was exploding. In that first year, California Institute of the Arts brought together an array of rebels and anarchists, with an inevitable tension between The Revolution and an accredited degree-granting, admission-charging institution.

The legendary Walt Disney once said, “I’ve always operated like the princes of Serendip . . . who went on quests not knowing what they would find.” Viewed as a middle-brow entertainment mogul, Disney was in fact a visionary and futurist (very much in line with 2020Visions). “[S]ome of our most important discoveries,” he continued, “have come from scientists who were searching for something else.”

A 1963 imagining of the future multimedia CalArts by Disney Studios (for fundraising purposes). Image by Heritage Auctions, HA.com.

Experimentation runs deep in CalArts’ DNA. Animator, producer and theme-park inventor Walt Disney had the novel vision of bringing all arts under one roof. When the Imagineer Extraordinaire died in 1966, his heirs, trying to bring “Walt’s dream” into fruition, hired East Coast educators with rising reputations, Robert Corrigan and his provost, Herb Blau, to assemble a well-funded institute just northeast of Los Angeles. However, buoyed by late 1960s hubris, the two had their own dream: a community full of revolutionary synergy, like legendary art centers Bauhaus and Black Mountain College. At the same time, the counterculture had its own radical dreams: that free love and thought would blossom once the Establishment blew up.

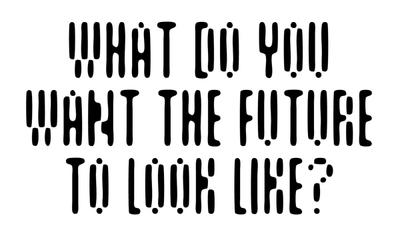

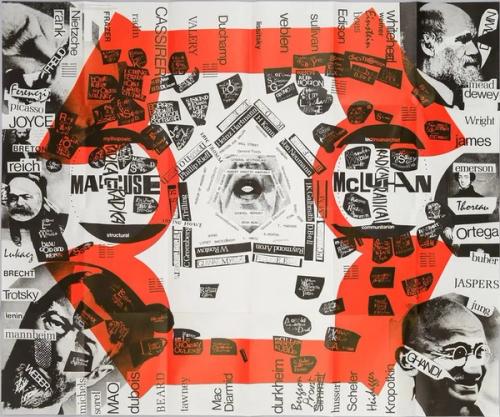

Fresh out of public high school, I somehow ended up enrolled in what was called the School of Critical Studies—the liberal arts component included to make accreditation possible. Typically, Maurice Stein, fresh from Brandeis, its radical head, had just co-published Blueprint for Counter Education: posters intended as a portable learning environment. (Subtitle: “The Revolution Starts Here.”) With the magical thinking of the time, osmosis would take place. “Stare at your walls,” Stein intoned. “You might learn something for a change.” In psychedelic Constructivist style, the visual quasi-bibliography mapped patterns between radical thought and art practices.

Blueprint for Counter Education – Maurice Stein, Larry Miller/ Designer Marshall Henrichs

Education would be reinvented! Meanwhile, art was dematerializing—in an anti-capitalist spirit, to pure concept, creating Polaroids and scraps of paper you couldn’t “sell.” Painting had been declared dead; conceptualist John Baldessari taught post-studio art, handing students a list of actions to execute. Everything had to be rethought. The harmonic system in Western music was corrupt: Nazis loved music, and it certainly hadn’t improved them. Electronic music embraced technology; world music from around the globe—Ghana, South and North India—would bring people together. And cinema was “expanding” into something called video art.

Alan Kaprow, the inventor of Happenings, was Associate Dean of the Art School and mentored many students.

By the second year, Stein and Blau were fired, the rebels and institution builders forged an uneasy truce, and the school moved into its modernist headquarters in Valencia, its opening delayed by a major earthquake. Yet, beyond the “wild-and-crazy” anecdotes (nude swimming in the pool; a faculty member taking his clothes off during a board meeting), there was the beating, courageous heart of something bold and future-looking. A design department devoted to environmental science; a modular theatre physically adjusting to the demands of esoteric performances.

The early 1970s were, in a pleasantly hip way, sexist; those on the vanguard of experimentation were young men. (It was questioned whether a woman could be a “great artist.”) Another revolution was ushered into the Valencia campus when the firebrand Judy Chicago, at the invitation of Miriam Shapiro, whose husband ran the Art School, moved her Feminist Art Program there—the first of its kind anywhere.

Judy Chicago, Immolation, from Women and Smoke, 1972. Fireworks performance in the California desert. Courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco, © Judy Chicago / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph courtesy of Through the Flower Archives

Beneath it all was the belief and the hope that art, taking risks, can transform society. Students were invited to constantly break rules. Authenticity over authority. CalArts struggled mightily between institutional needs and radical innovation—it still does. But there remains an openness that provides entry to all sorts of possibilities. Today when artists are much more directly engaged with civic issues, CalArts is perfectly positioned to draw from this DNA to take on a marriage of art and future-looking innovations.

Because of its dreams and dreamers, 2020Visions is proud to partner with CalArts.

— Carey Lovelace (BFA Music, 1975)

Listen: “CalArts’ Early Days”: An Interview with Iconic Designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville

Founder of CalArts’ Feminist Design Program, in 1970 De Bretteville designed brilliantly unorthodox materials recruiting students to a new experimental school with a world-class faculty—and witnessed its beginnings first-hand.

De Bretteville’s Feminist Design Workshop, c. 1973. Courtesy CalArts archive.

Future Cultural Laboratory

By Ravi Rajan, President of California Institute of the Arts

I’m often asked what my vision is for CalArts. Truth be told, it is the same as the vision I have for society: to embrace a new paradigm that sustains the strengths of what we do now, and sheds that which encumbers us. (For CalArts, it can be at times the educational complex that does most of the encumbering.)

Keep Reading: President Ravi Rajan’s reflections on CalArts’ future possibilities.

Educational Centers as Incubators for World-Changing Movements

CalArts was inspired by the visionary Bauhaus and Black Mountain College, charismatic locales legendary not just as sites for daring and experimental teaching, but where artist-faculty cross-pollinations advanced society forward.

Oskar Schlemmer. Group photo of Triadisches Ballett, 1927. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Before it was shut down by Hitler in 1933, the legendary German Bauhaus (founded 1919) brought together iconic painters, architects, and designers including Walter Gropius, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, László Moholy-Nagy, Oskar Schlemmer, and Mies van der Rohe who, famously combining form with function, together created its Bauhaus style, one of the most influential developments in modern design. With its pure forms and austere simplicity, in the belief they were harnessing forces shaping a better future, they combined crafts with fine arts, and mass production with individual artistic vision.

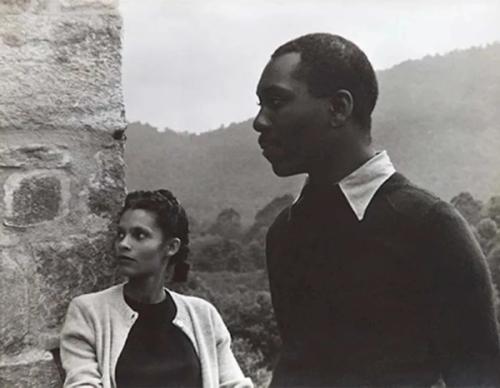

Gwendolyn Knight and Jacob Lawrence at Black Mountain College, 1946. (Photographer unknown)

Bauhaus alum such as Josef and Anni Albers and Walter Gropius, ended up migrating to Black Mountain College in the North Carolina mountains, which opened the year the Berlin institute closed. Like the future CalArts, it was an experiment in education, organized around holistic learning, students empowered to undertake their own formation as citizens of the world. They were to decide themselves when they were ready to graduate; few did.

Just as European modernism coalesced around the Bauhaus, Black Mountain was a melting pot for John Cage-influenced life-as-art approaches, visionary trends that promoted, as Holland Cotter put it, “the dream of art as a lived condition rather than a hoarded possession.” A small, shifting faculty included Buckminster Fuller, Robert Motherwell, Jacob Lawrence, Charles Olson, and Merce Cunningham among many others, and students included Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, Sue Weil, Dorothea Rockburne, Ruth Asawa, to name a few.

John Baldessari, Teaching a Plant the Alphabet, 1972, video. The Conceptual painter’s career blossomed while teaching at CalArts, many of his students going on to become the celebrated 1980s Pictures Generation — ironically, returning to the very painting and imagery CalArts teachers advocated against.

Similarly, CalArts sought to create a vibrant, anarchic community, including the cream of Fluxus—Happenings inventor Kaprow, Nam June Paik, Dick Higgins, Emmet Williams, Allison Knowles, choreographer Simone Forti, composer James Tenney—as well as conceptual artists Baldessari, Doug Huebler, and Wolfgang Stoehle, and many others, fostering an anarchy-riven climate that produced another social turning point with its dizzyingly diverse list of celebrated students. Arguably ushering in Post-Modernism, Pictures Generation and Feminist artists were followed, in later years, by such photographers as Carrie Mae Weems, painters as Mark Bradford, installation artists as Mike Kelly, and film directors as Tim Burton.

The Modular Theatre, built in 1973, innovative in its day, was designed with four integrated systems, all moveable: floor, walls, lights, and hoists for flying scenery.

CalArts Imaginators: The New Generation

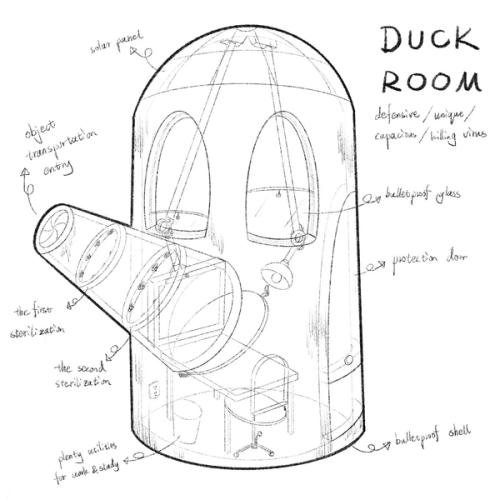

Moon Wang’s Duck Room

2020Visions is dedicated to harnessing the artistic imagination to create new paradigms for society. We invited CalArts students to dream forward. One submission was Moon Wang’s Duck Room, that “…may appear in the future and help people work or study in isolation. Inspired by our current quarantined life and fear of the virus…a cool room where people can study and work safely.”

More About CalArts and its Inspirations:

A Community of Artists: Radical Pedagogy at CalArts, 1969-72 by Janet Sarbanes

Womanhouse. Judy Chicago; Miriam Schapiro; California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Program, 1972.

“A Very Unusual School”: Bauhaus, Black Mountain College, and Today by Diana C. Stoll

The Bauhaus’ Most Iconic Designs, Explained by Milly Burroughs